Gene expressions measured as scRNA-Seq of 2622 human peripheral blood mononuclear cells data is available from the Seurat R package Satija et al. (2015). The paper web site has code to extract and pre-process the data, which follow the tutorial at https://satijalab.org/seurat/articles/pbmc3k_tutorial.html. The processed data, containing the first 50 PCs is provided with the book, as pbmc_pca_50.rds.

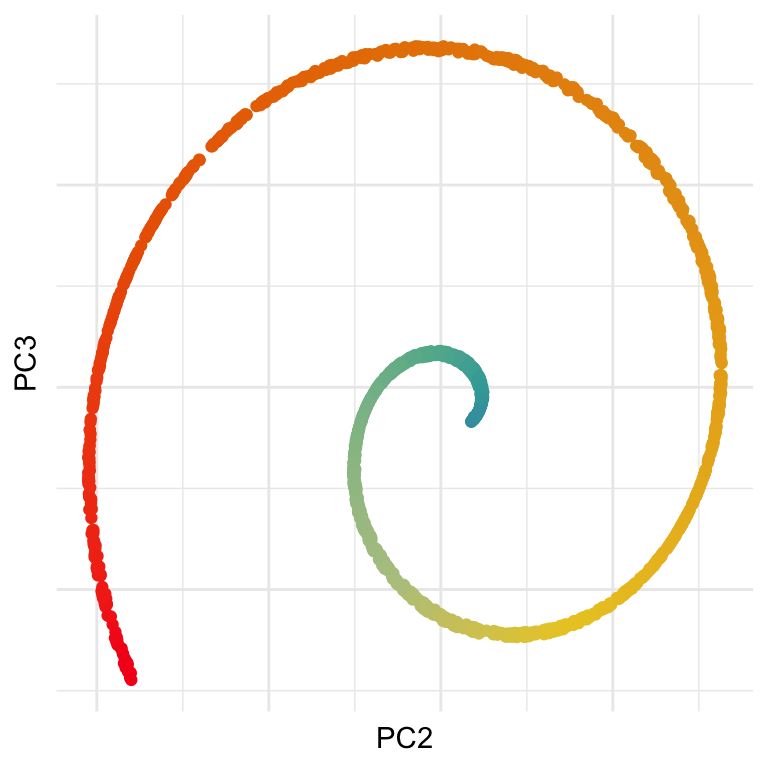

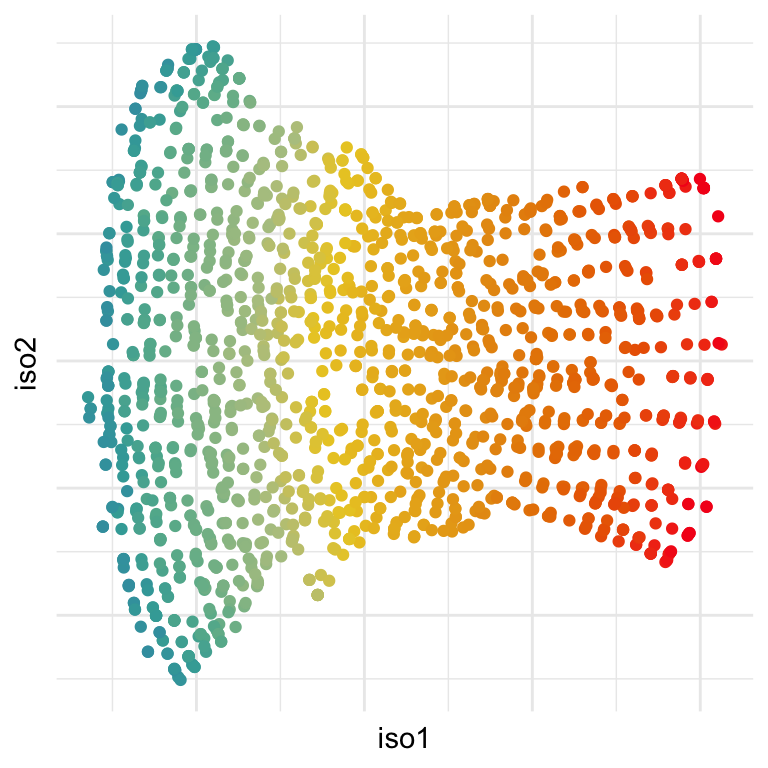

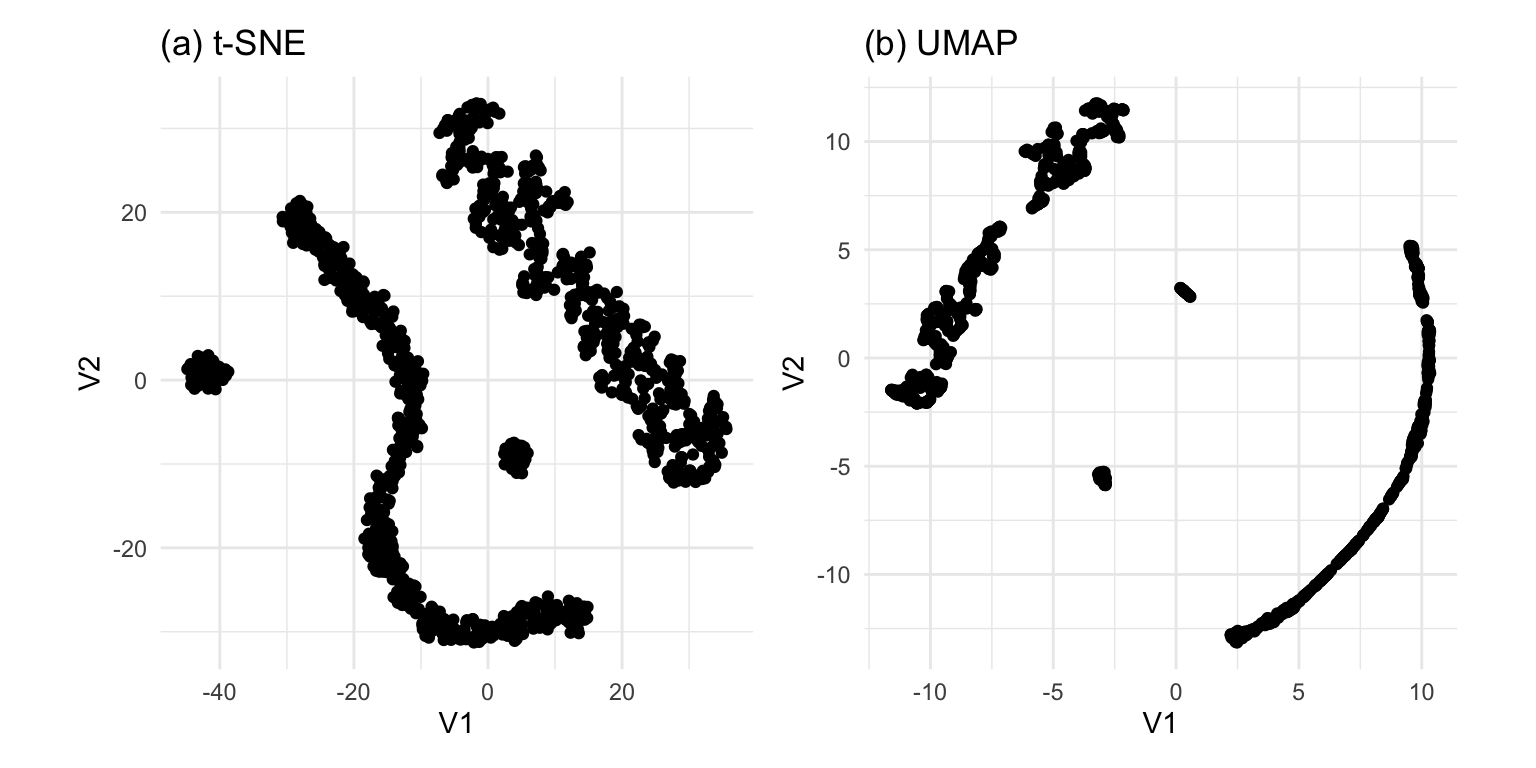

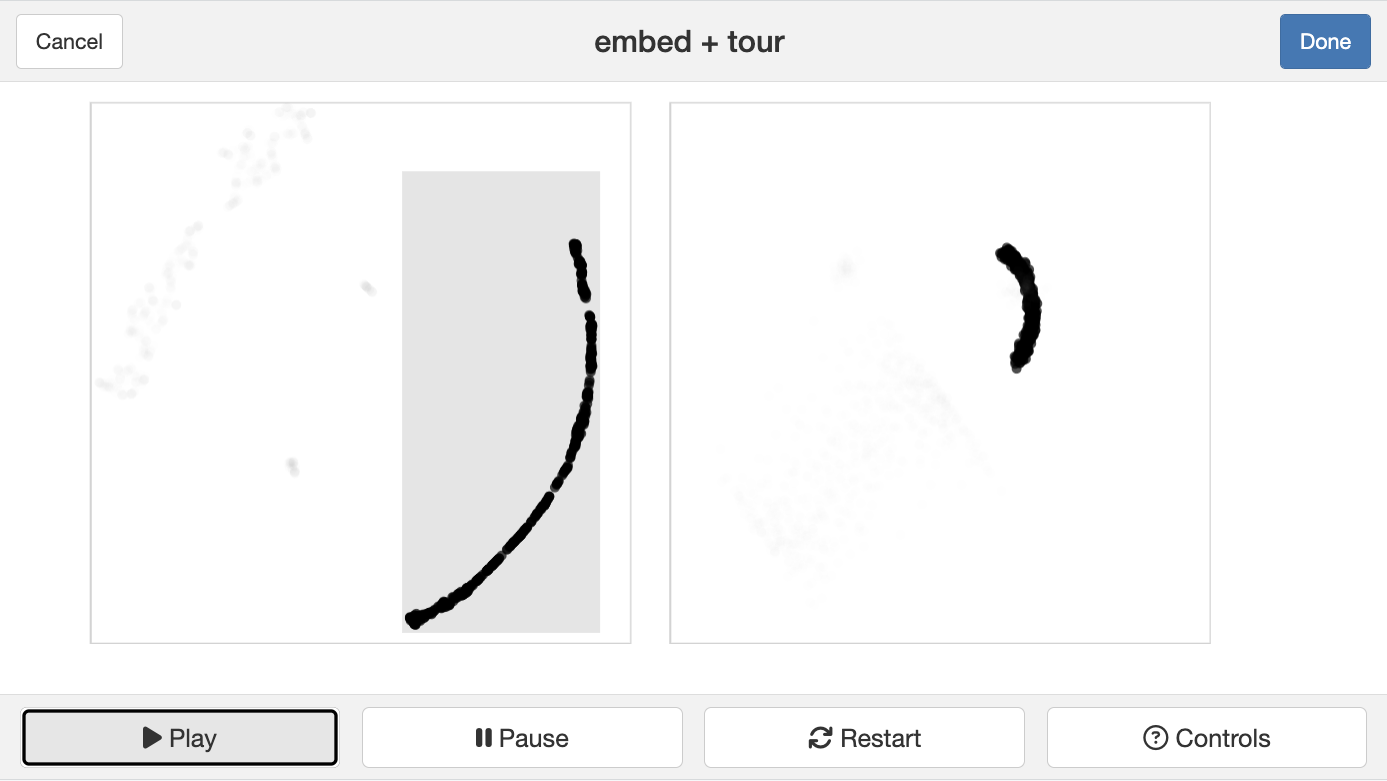

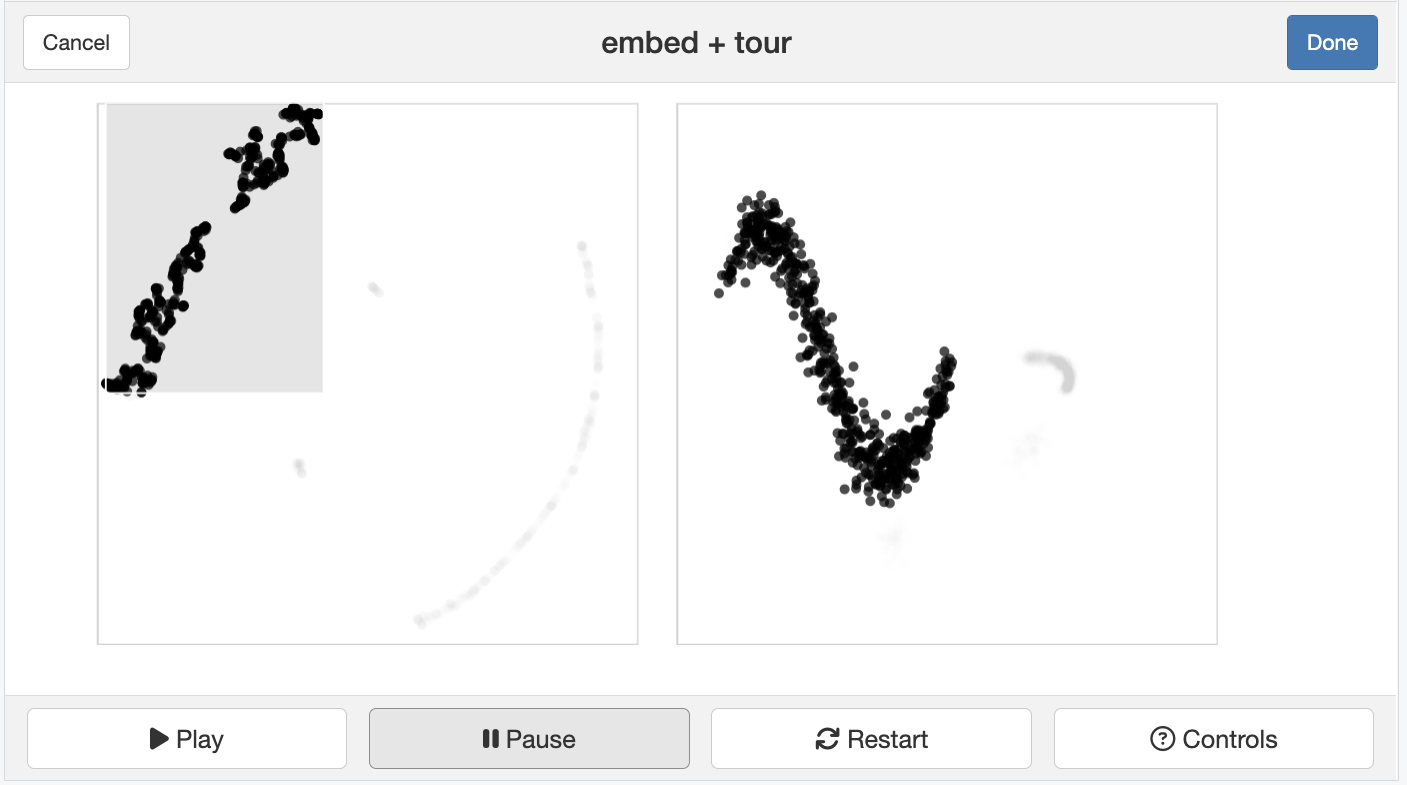

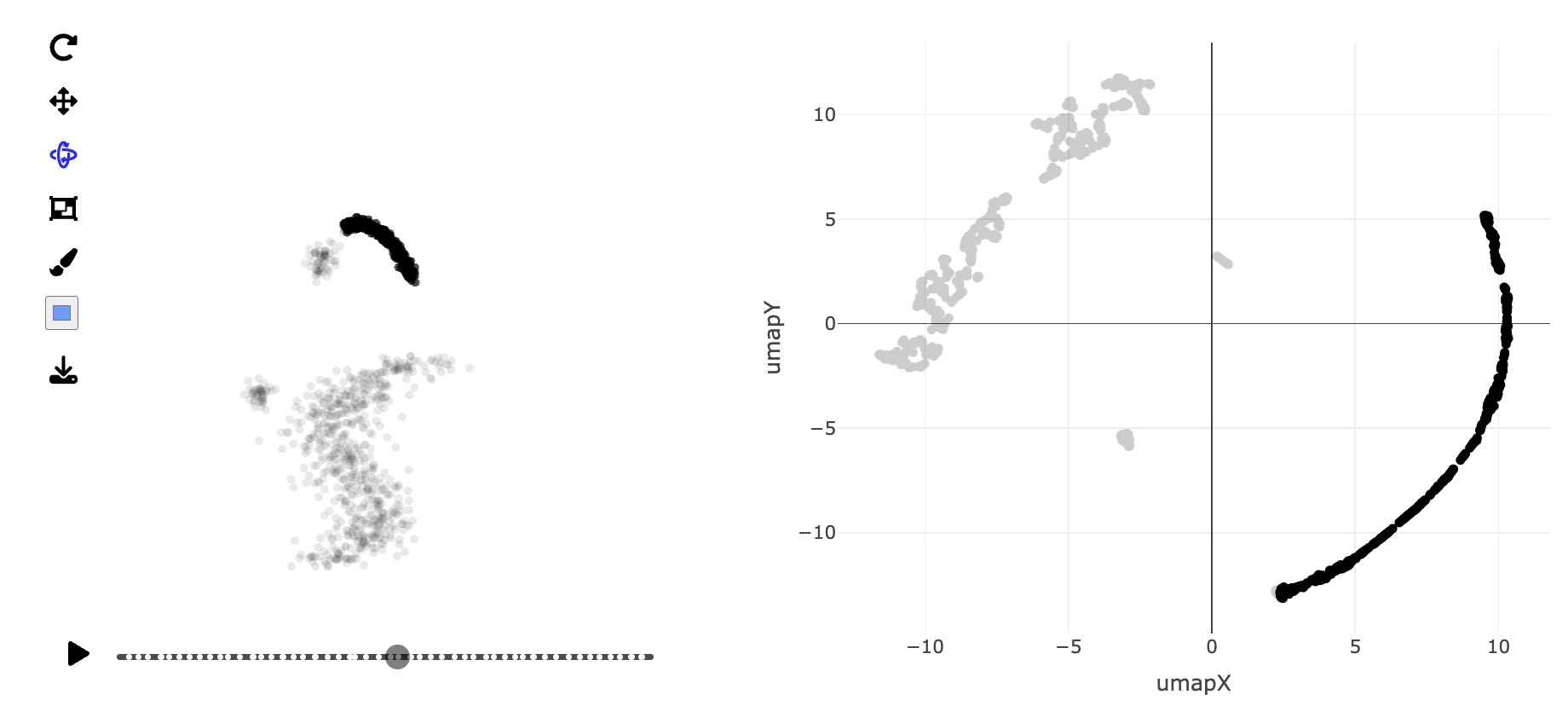

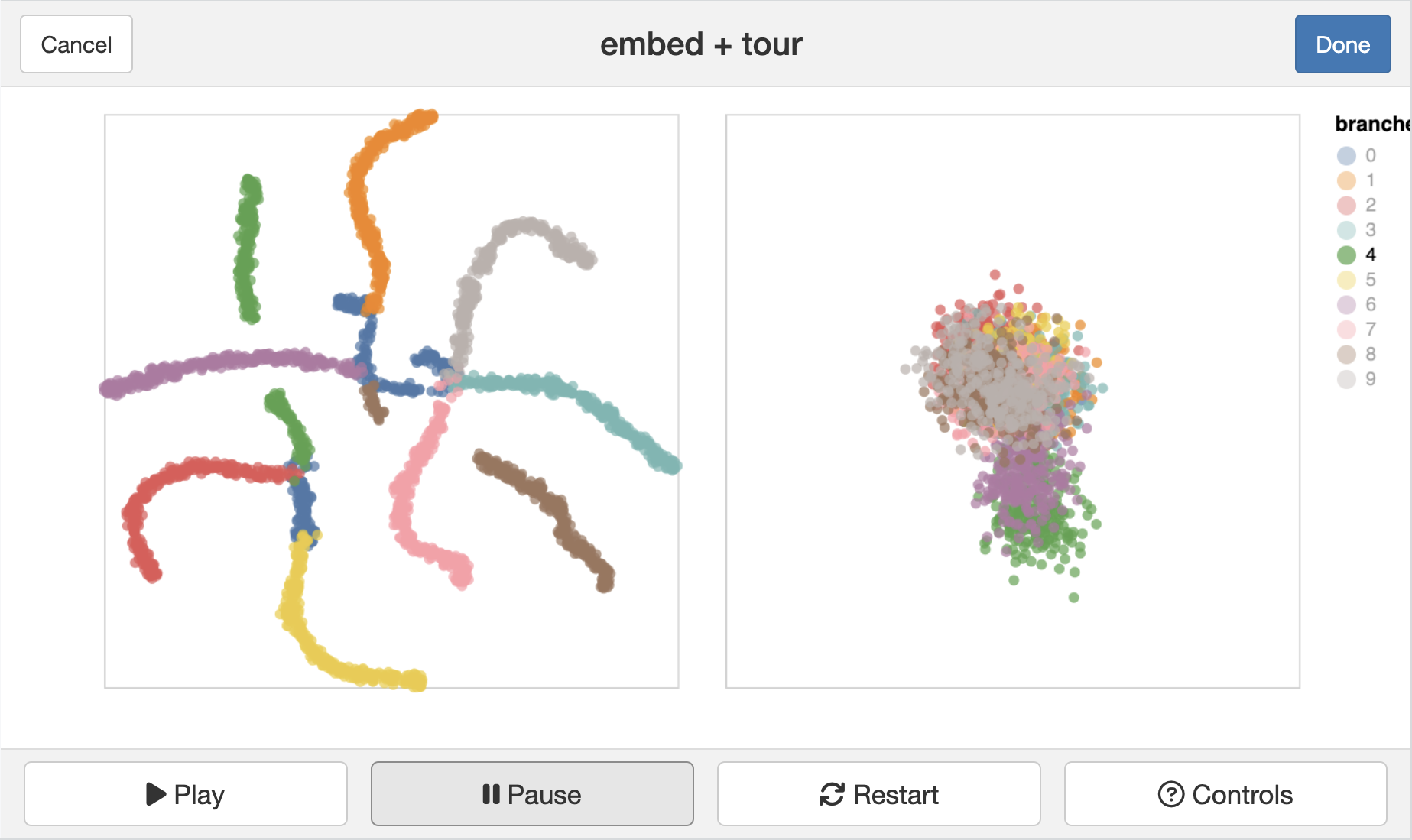

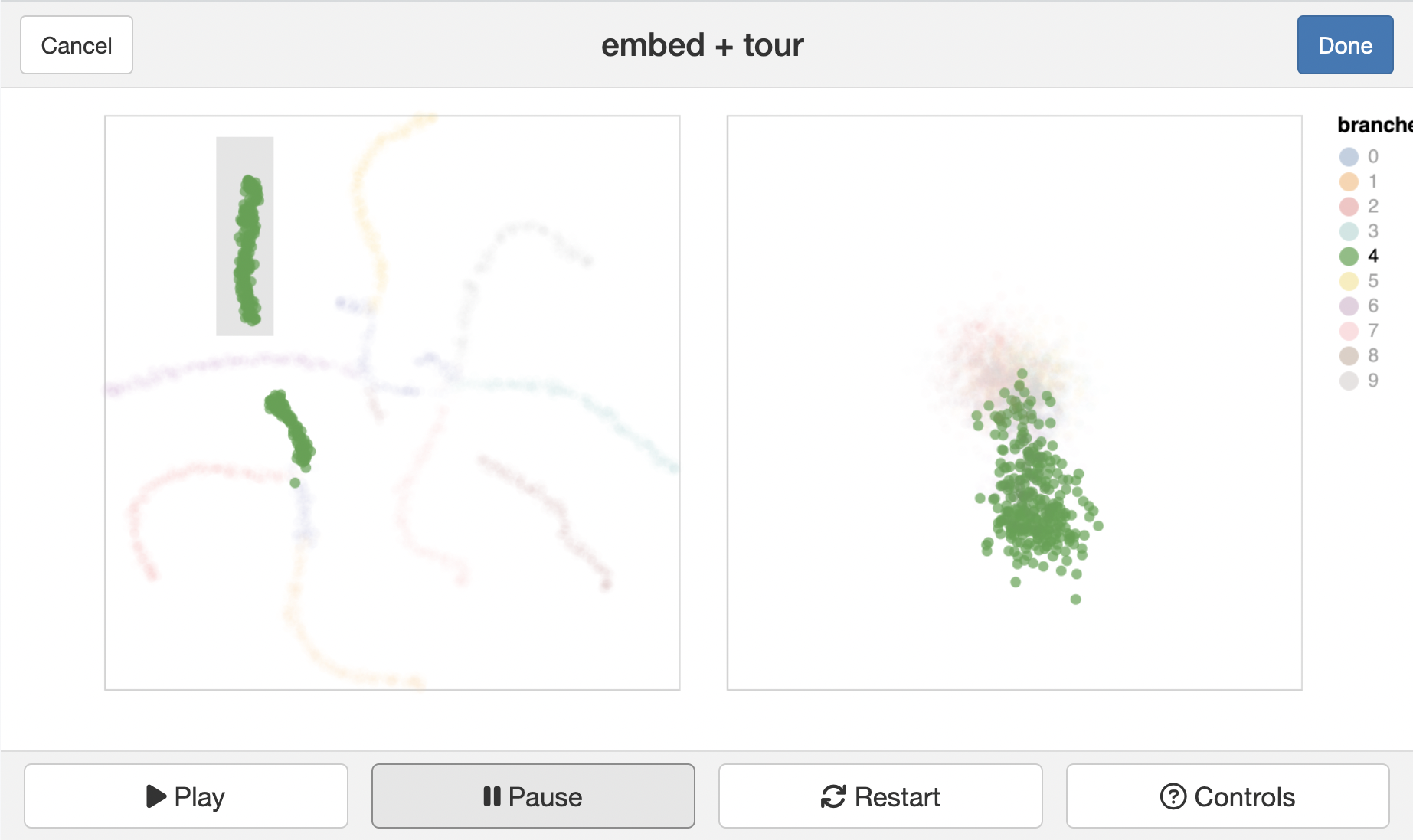

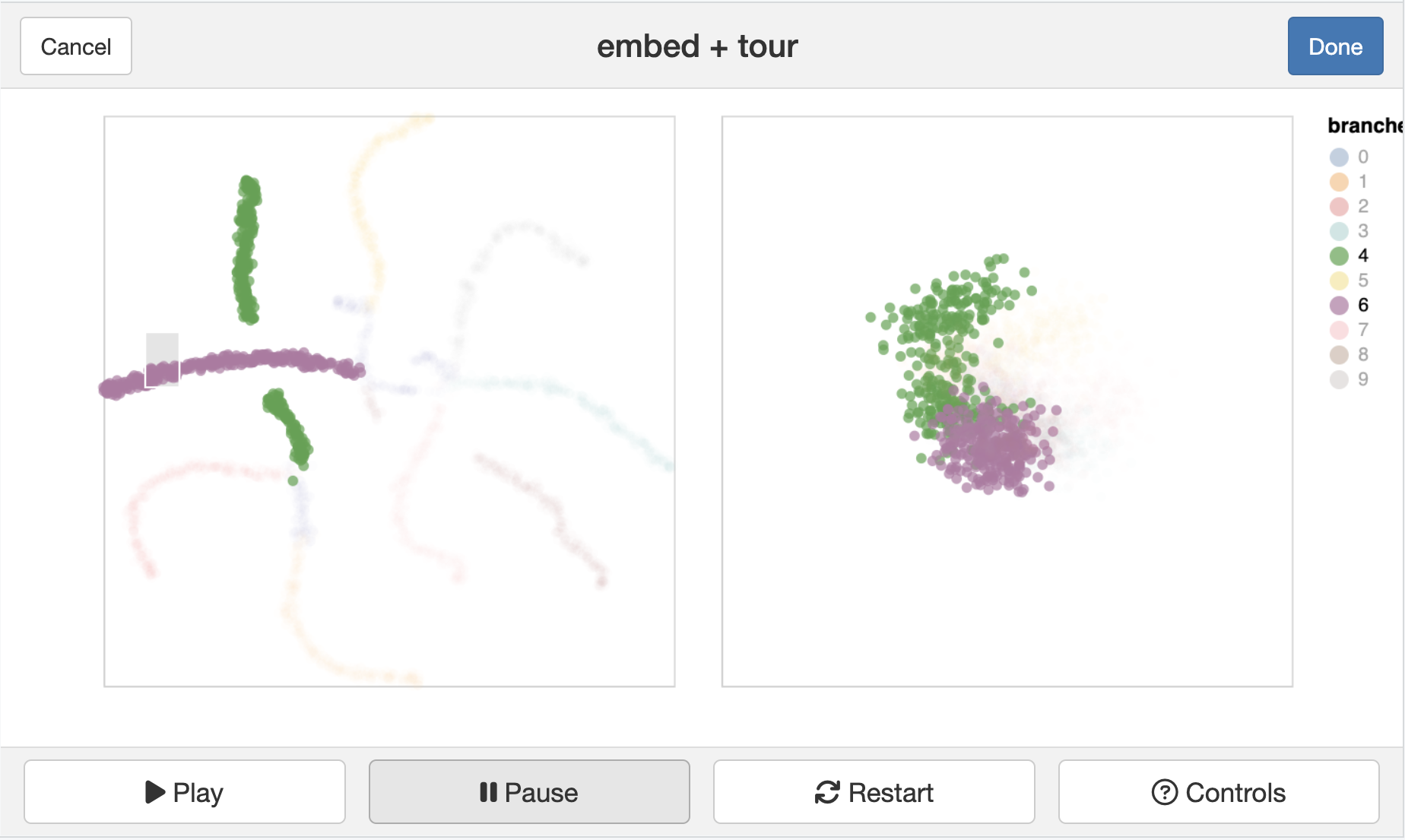

Generate the t-SNE and UMAP representations of the first 9 PCs of data, using their default settings. They should be quite different. (We use 9 PCs because the scree plot in the data pre-processing suggests that 15 is too many.) Based on your examination of the data in a tour, which method yields the more accurate representation? Explain what the structure in the 2D is relative to that seen in the tour.

Abbott, E. (1884). Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions. Dover Publications.

Ahlberg, C., Williamson, C., & Shneiderman, B. (1991). Dynamic Queries for Information Exploration: An Implementation and Evaluation. ACM CHI ‘92 Conference Proceedings, 619–626.

Allaire, J., & Chollet, F. (2023).

keras: R interface to Keras.

https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=keras

Anderson, E. (1957). A Semigraphical Method for the Analysis of Complex Problems. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, 13, 923–927.

Andrews, D. F. (1972). Plots of High-dimensional Data. Biometrics, 28, 125–136.

Andrews, D. F., Gnanadesikan, R., & Warner, J. L. (1971). Transformations of Multivariate Data. Biometrics, 27, 825–840.

Anselin, L., & Bao, S. (1997). Exploratory Spatial Data Analysis Linking SpaceStat and ArcView. In M. M. Fischer & A. Getis (Eds.), Recent Developments in Spatial Analysis (pp. 35–59). Springer.

Arnold, J. B. (2024).

ggthemes: Extra Themes, Scales and Geoms for ggplot2.

https://jrnold.github.io/ggthemes/

Asimov, D. (1985). The Grand Tour: A Tool for Viewing Multidimensional Data. SIAM Journal of Scientific and Statistical Computing, 6(1), 128–143.

Batsaikhan, Z., Cook, D., & Laa, U. (2023).

Frame to Frame Interpolation for High-dimensional Data Visualisation using the woylier package.

https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2311.08181

Batsaikhan, Z., Cook, D., & Laa, U. (2024).

woylier: Alternative Tour Frame Interpolation Method.

https://numbats.github.io/woylier/

Becker, R. A., & Chambers, J. M. (1984). S: An Environment for Data Analysis and Graphics. Wadsworth.

Becker, R. A., & Cleveland, W. S. (1988). Brushing Scatterplots (W. S. Cleveland & M. E. McGill, Eds.; pp. 201–224). Wadsworth.

Becker, R., Cleveland, W. S., & Shyu, M.-J. (1996). The Visual Design and Control of Trellis Displays. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics, 6(1), 123–155.

Bederson, B. B., & Schneiderman, B. (2003). The Craft of Information Visualization: Readings and Reflections. Morgan Kaufmann.

Bellman, R. (1961). Adaptive Control Processes: A Guided Tour.

Bickel, P. J., Kur, G., & Nadler, B. (2018). Projection

Pursuit in

High

Dimensions.

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences,

115, 9151–9156.

https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1801177115

Bishop, C. M. (2006). Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning. Springer.

Boehmke, B., & Greenwell, B. M. (2019).

Hands-On Machine Learning with R (1st ed.). Chapman; Hall/CRC.

https://doi.org/10.1201/9780367816377

Boelaert, J., Ollion, E., & Sodoge, J. (2022).

aweSOM: Interactive Self-Organizing Maps.

https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=aweSOM

Bonneau, G.-P., Ertl, T., & Nielson, G. M. (Eds.). (2006). Scientific Visualization: The Visual Extraction of Knowledge from Data. Springer.

Borg, I., & Groenen, P. J. F. (2005). Modern Multidimensional Scaling. Springer.

Breiman, L. (2001). Random Forests. Machine Learning, 45(1), 5–32.

Breiman, L., Cutler, A., Liaw, A., & Wiener, M. (2022).

randomForest: Breiman and Cutler’s Random Forests for classification and Regression.

https://www.stat.berkeley.edu/~breiman/RandomForests/

Breiman, L., Friedman, J., Olshen, C., & Stone, C. (1984). Classification and Regression Trees. Wadsworth; Brooks/Cole.

Buja, A. (1996). Interactive Graphical Methods in the Analysis of Customer Panel Data: Comment. Journal of Business & Economic Statistics, 14(1), 128–129.

Buja, A., & Asimov, D. (1986). Grand Tour Methods: An Outline. Computing Science and Statistics, 17, 63–67.

Buja, A., Asimov, D., Hurley, C., & McDonald, J. A. (1988). Elements of a Viewing Pipeline for Data Analysis (W. S. Cleveland & M. E. McGill, Eds.; pp. 277–308). Wadsworth.

Buja, A., Cook, D., Asimov, D., & Hurley, C. (2005). Computational Methods for High-Dimensional Rotations in Data Visualization. In C. R. Rao, E. J. Wegman, & J. L. Solka (Eds.), Handbook of Statistics: Data Mining and Visualization (pp. 391–414). Elsevier/North-Holland.

Buja, A., Cook, D., & Swayne, D. (1996). Interactive High-Dimensional Data Visualization. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics, 5(1), 78–99.

Buja, A., Hurley, C., & McDonald, J. A. (1986). A Data Viewer for Multivariate Data. Computing Science and Statistics, 17(1), 171–174.

Buja, A., & Swayne, D. F. (2002). Visualization Methodology for Multidimensional Scaling. Journal of Classification, 19(1), 7–43.

Buja, A., Swayne, D. F., Littman, M. L., Dean, N., Hofmann, H., & Chen, L. (2008). Data

Visualization with

Multidimensional

Scaling.

Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics,

17(2), 444–472.

https://doi.org/10.1198/106186008X318440

Buja, A., & Tukey, P. (Eds.). (1991). Computing and Graphics in Statistics. Springer-Verlag.

Butler, A., Hoffman, P., Smibert, P., Papalexi, E., & Satija, R. (2018). Integrating

Single-

Cell

Transcriptomic

Data

Across

Different

Conditions,

Technologies, and

Species.

Nature Biotechnology,

36, 411–420.

https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.4096

Card, S. K., Mackinlay, J. D., & Schneiderman, B. (1999). Readings in Information Visualization. Morgan Kaufmann Publishers.

Carr, D. B., Wegman, E. J., & Luo, Q. (1996). ExplorN: Design Considerations Past and Present (Technical Report No. 129). Center for Computational Statistics, George Mason University.

Chatfield, C. (1995). Problem Solving: A Statistician’s Guide. Chapman; Hall/CRC Press.

Chen, C.-H., Härdle, W., & Unwin, A. (Eds.). (2007).

Handbook of Data Visualization. Springer.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-33037-0

Chen, Z., Wang, C., Huang, S., Shi, Y., & Xi, R. (2024). Directly

Selecting

Cell-type

Marker

Genes for

Single-cell

Clustering

Analyses.

Cell Reports Methods,

4, 100810.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crmeth.2024.100810

Cheng, B., & Titterington, M. (1994). Neural Networks: A Review from a Statistical Perspective. Statistical Science, 9(1), 2–30.

Cheng, J., & Sievert, C. (2023).

crosstalk: Inter-Widget Interactivity for HTML Widgets.

https://rstudio.github.io/crosstalk/

Chernoff, H. (1973). The Use of Faces to Represent Points in \(k\)-dimensional Space Graphically. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 68, 361–368.

Cleveland, W. S. (1979). Robust Locally Weighted Regression and Smoothing Scatterplots. Journal of American Statistics Association, 74, 829–836.

Cleveland, W. S. (1993). Visualizing Data. Hobart Press.

Cleveland, W. S., & McGill, M. E. (Eds.). (1988). Dynamic Graphics for Statistics. Wadsworth.

Cook, D., & Buja, A. (1997). Manual Controls For High-Dimensional Data Projections. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics, 6(4), 464–480.

Cook, D., Buja, A., & Cabrera, J. (1993). Projection Pursuit Indexes Based on Orthonormal Function Expansions. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics, 2(3), 225–250.

Cook, D., Buja, A., Cabrera, J., & Hurley, C. (1995). Grand Tour and Projection Pursuit. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics, 4(3), 155–172.

Cook, D., Hofmann, H., Lee, E.-K., Yang, H., Nikolau, B., & Wurtele, E. (2007). Exploring Gene Expression Data, Using Plots. Journal of Data Science, 5(2), 151–182.

Cook, D., & Laa, U. (2025).

mulgar: Functions for Pre-Processing Data for Multivariate data Visualisation using Tours.

https://dicook.github.io/mulgar/

Cook, D., Lee, E.-K., Buja, A., & Wickham, H. (2006).

Grand

Tours,

Projection

Pursuit

Guided

Tours and

Manual

Controls. In C.-H. Chen, W. Härdle, & A. Unwin (Eds.),

Handbook of Data Visualization. Springer.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-33037-0

Cook, D., Majure, J. J., Symanzik, J., & Cressie, N. (1996). Dynamic Graphics in a GIS: Exploring and Analyzing Multivariate Spatial Data using Linked Software. Computational Statistics: Special Issue on Computer Aided Analyses of Spatial Data, 11(4), 467–480.

Cook, D., & Swayne, D. F. (2007).

Interactive and Dynamic Graphics for Data Analysis: With R and GGobi. Springer-Verlag.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-71762-3

Cortes, C., Pregibon, D., & Volinsky, C. (2003). Computational Methods for Dynamic Graphs. Journal of Computational & Graphical Statistics, 12(4), 950–970.

Cortes, C., & Vapnik, V. N. (1995). Support-Vector Networks. Machine Learning, 20(3), 273–297.

d’Ocagne, M. (1885). Coordonnées Parallèles et Axiales: Méthode de Transformation Géométrique et Procédé Nouveau de Calcul Graphique dÉduits de la Considération des Coordonnées Paralléles. Gauthier-Villars.

Dalgaard, P. (2002). Introductory Statistics with R. Springer.

Dasu, T., Swayne, D. F., & Poole, D. (2005). Grouping Multivariate Time Series: A Case Study. Proceedings of the IEEE Workshop on Temporal Data Mining: Algorithms, Theory and Applications, in Conjunction with the Conference on Data Mining, Houston, November 27, 2005, 25–32.

de Vries, A., & Ripley, B. D. (2024).

ggdendro: Create Dendrograms and Tree Diagrams Using ggplot2.

https://andrie.github.io/ggdendro/

Department of Environment, Land, Water & Planning. (2019).

Fire Origins - Current and Historical.

https://discover.data.vic.gov.au/dataset/fire-origins-current-and-historical

Department of Environment, Land, Water & Planning. (2020a).

CFA - Fire Station.

https://discover.data.vic.gov.au/dataset/cfa-fire-station-vmfeat-geomark_point

Department of Environment, Land, Water & Planning. (2020b).

Recreation Sites.

https://discover.data.vic.gov.au/dataset/recreation-sites

Diaconis, P., & Freedman, D. (1984). Asymptotics of Graphical Projection Pursuit. Annals of Statistics, 12, 793–815.

Dolnicar, S., Grün, B., & Leisch, F. (2018).

Market Segmentation Analysis: Understanding it, Doing it, and Making it Useful (pp. 11–22).

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-8818-6_2

Dykes, J., MacEachren, A. M., & Kraak, M.-J. (2005). Exploring Geovisualization. Elsevier.

Emerson, J. W., Green, W. A., Schloerke, B., Crowley, J., Cook, D., Hofmann, H., & Wickham, H. (2013). The

Generalized

Pairs

Plot.

Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics,

22(1), 79–91.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10618600.2012.694762

Everitt, B. S., Landau, S., Leese, M., & Stahel, D. (2011). Cluster Analysis (5th ed). John Wiley; Sons, Ltd.

Fienberg, S. E. (1979). Graphical Methods in Statistics. Journal of American Statistical Association, 33(4), 165–178.

Fisher, R. A. (1936). The

Use of

Multiple

Measurements in

Taxonomic

Problems.

Annals of Eugenics,

7(2), 179–188.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-1809.1936.tb02137.x

Fisherkeller, M. A., Friedman, J. H., & Tukey, J. W. (1973).

PRIM-9, an Interactive Multidimensional Data Display and Analysis System.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B7XoW2qiFUA

Fisherkeller, M. A., Friedman, J. H., & Tukey, J. W. (1974). PRIM-9, an Interactive Multidimensional Data Display and Analysis System. In W. S. Cleveland (Ed.), The collected works of john w. Tukey: Graphics 1965-1985, volume v (pp. 340–346).

Forbes, J., Cook, D., & Hyndman, R. J. (2020). Spatial modelling of the two-party preferred vote in australian federal elections: 2001–2016.

Australian & New Zealand Journal of Statistics,

62(2), 168–185. https://doi.org/

https://doi.org/10.1111/anzs.12292

Ford, B. J. (1992). Images of Science: A History of Scientific Illustration. The British Library.

Forgy, E. (1965). Cluster Analysis of Multivariate Data: Efficiency versus Interpretability of Classification. Biometrics, 21(3), 768–769.

Fraley, C., & Raftery, A. E. (2002). Model-based

Clustering,

Discriminant

Analysis,

Density

Estimation.

Journal of the American Statistical Association,

97, 611–631.

https://doi.org/10.1198/016214502760047131

Fraley, C., Raftery, A. E., & Scrucca, L. (2024).

Mclust: Gaussian mixture modelling for model-based clustering, classification, and density estimation.

https://mclust-org.github.io/mclust/

Friedman, J. H. (1987). Exploratory Projection Pursuit. Journal of American Statistical Association, 82, 249–266.

Friedman, J. H., & Tukey, J. W. (1974). A Projection Pursuit Algorithm for Exploratory Data Analysis. IEEE Transactions on Computing C, 23, 881–889.

Friendly, M., & Denis, D. J. (2004). Milestones in the History of Thematic Cartography, Statistical Graphics, and Data Visualization. http://www.math.yorku.ca/SCS/Gallery/milestone/.

Fritsch, S., Guenther, F., & Wright, M. N. (2019).

neuralnet: Training of Neural Networks.

https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=neuralnet

Furnas, G. W., & Buja, A. (1994). Prosection Views: Dimensional Inference Through Sections and Projections. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics, 3(4), 323–385.

Gabriel, K. R. (1971). The Biplot Graphical Display of Matrices with Applications to Principal Component Analysis. Biometrika, 58, 453–467.

Gentle, J. E., Härdle, W., & Mori, Y. (Eds.). (2004). Handbook of Computational Statistics: Concepts and Methods. Springer.

Giordani, P., Ferraro, M. B., & Martella, F. (2020).

An Introduction to Clustering with R. Springer Singapore.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-0553-5

Glover, D. M., & Hopke, P. K. (1992). Exploration of Multivariate Chemical Data by Projection Pursuit. Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems, 16, 45–59.

Good, P. (2005). Permutation, Parametric, and Bootstrap Tests of Hypotheses. Springer.

Gower, J. C., & Hand, D. J. (1996). Biplots. Chapman; Hall.

Gruen, B. (2024). CRAN Task View: Cluster Analysis & Finite Mixture Models (Version 2024-08-20). https://cran.r-project.org/web/views/Cluster.html.

Hajibaba, H., Karlsson, L., & Dolnicar, S. (2016). Residents Open Their Homes to Tourists When Disaster Strikes. Journal of Travel Research, 56(8), 1065–1078.

Hansen, C., & Johnson, C. R. (2004). Visualization Handbook. Academic Press.

Hao, Y., Hao, S., Andersen-Nissen, E., III, W. M. M., Zheng, S., Butler, A., Lee, M. J., Wilk, A. J., Darby, C., Zagar, M., Hoffman, P., Stoeckius, M., Papalexi, E., Mimitou, E. P., Jain, J., Srivastava, A., Stuart, T., Fleming, L. B., Yeung, B., … Satija, R. (2021). Integrated

Analysis of

Multimodal

Single-

Cell

Data.

Cell.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2021.04.048

Harrison, P. (2023).

langevitour:

Smooth

Interactive

Touring of

High

Dimensions,

Demonstrated with

scRNA-Seq Data.

The R Journal,

15, 206–219.

https://doi.org/10.32614/RJ-2023-046

Harrison, P. (2024).

Langevitour: Langevin tour.

https://logarithmic.net/langevitour/

Hart, C., & Wang, E. (2024).

detourr: Portable and Performant Tour Animations.

https://casperhart.github.io/detourr/

Hartigan, J. A., & Kleiner, B. (1981). Mosaics for Contingency Tables. Computer Science and Statistics: Proceedings of the 13th Symposium on the Interface, 268–273.

Hartigan, J., & Kleiner, B. (1984). A Mosaic of Television Ratings. The American Statistician, 38, 32–35.

Haslett, J., Bradley, R., Craig, P., Unwin, A., & Wills, G. (1991). Dynamic Graphics for Exploring Spatial Data with Application to Locating Global and Local Anomalies. The American Statistician, 45(3), 234–242.

Hastie, T., Tibshirani, R., & Friedman, J. (2001). The Elements of Statistical Learning. Springer.

Hennig, C. (2024).

fpc: Flexible Procedures for Clustering.

https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=fpc

Hennig, C., Meila, M., Murtagh, F., & Rocci, R. (2015).

Handbook of Cluster Analysis (1st ed.). Chapman; Hall/CRC.

https://doi.org/10.1201/b19706

Hofmann, H. (2001). Graphical Tools for the Exploration of Multivariate Categorical Data. Books on Demand.

Hofmann, H. (2003). Constructing and Reading Mosaicplots. Computational Statistics and Data Analysis, 43(4), 565–580.

Hofmann, H., & Theus, M. (1998). Selection Sequences in MANET. Computational Statistics, 13(1), 77–87.

Horikoshi, M., & Tang, Y. (2018).

ggfortify: Data Visualization Tools for Statistical Analysis Results.

https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=ggfortify

Horikoshi, M., & Tang, Y. (2024).

ggfortify: Data Visualization Tools for Statistical Analysis Results.

https://github.com/sinhrks/ggfortify

Horst, A. M., Hill, A. P., & Gorman, K. B. (2022). Palmer

Archipelago

Penguins

Data in the palmerpenguins

R Package -

An

Alternative to

Anderson’s

Irises.

The R Journal,

14, 244–254.

https://doi.org/10.32614/RJ-2022-020

Horst, A., Hill, A., & Gorman, K. (2022).

palmerpenguins: Palmer Archipelago (Antarctica) Penguin Data.

https://allisonhorst.github.io/palmerpenguins/

Hotelling, H. (1933). Analysis of a

Complex of

Statistical

Variables into

Principal

Components.

Journal of Educational Psychology,

24(6), 417--441.

https://doi.org/10.1037/h0071325

Huber, P. J. (1985). Projection Pursuit (with discussion). Annals of Statistics, 13, 435–525.

Hurley, C. (1987). The Data Viewer: An Interactive Program for Data Analysis [PhD thesis]. University of Washington.

Iannone, R., Cheng, J., Schloerke, B., Hughes, E., Lauer, A., & Seo, J. (2024).

Gt: Easily create presentation-ready display tables.

https://gt.rstudio.com

Ihaka, R., & Gentleman, R. (1996). R: A Language for Data Analysis and Graphics. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics, 5, 299–314.

Ihaka, R., Murrell, P., Hornik, K., Fisher, J. C., Stauffer, R., Wilke, C. O., McWhite, C. D., & Zeileis, A. (2024).

colorspace: A Toolbox for Manipulating and Assessing Colors and Palettes.

https://colorspace.R-Forge.R-project.org/

Inselberg, A. (1985). The Plane with Parallel Coordinates. The Visual Computer, 1, 69–91.

Johnson, D., & Travis, J. (2007). Flatland: The Movie. https://round-drum-w7xh.squarespace.com/our-story.

Johnson, R. A., & Wichern, D. W. (2002). Applied Multivariate Statistical Analysis (5th ed). Prentice-Hall.

Jolliffe, I. T., & Cadima, J. (2016). Principal

Component

Analysis: A

Review and

Recent

Developments.

Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A,

374, 20150202.

https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2015.0202

Jones, M. C., & Sibson, R. (1987). What is Projection Pursuit? (With discussion). Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series A, 150, 1–36.

Kandanaarachchi, S. (2022).

dobin: Dimension Reduction for Outlier Detection.

https://sevvandi.github.io/dobin/

Kandanaarachchi, S., & Hyndman, R. J. (2021). Dimension

Reduction for

Outlier

Detection

Using DOBIN.

Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics,

30(1), 204–219. https://doi.org/

https://doi.org/10.1080/10618600.2020.1807353

Kassambara, A. (2017). Practical Guide to Cluster Analysis in R: Unsupervised Machine Learning. STHDA.

Kassambara, A. (2023).

ggpubr: ggplot2 Based Publication Ready Plots.

https://rpkgs.datanovia.com/ggpubr/

Kohonen, T. (2001). Self-Organizing Maps (3rd ed). Springer.

Koschat, M. A., & Swayne, D. F. (1996). Interactive Graphical Methods in the Analysis of Customer Panel Data (with discussion). Journal of Business and Economic Statistics, 14(1), 113–132.

Krijthe, J. (2023).

Rtsne: T-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding using a Barnes-hut Implementation.

https://github.com/jkrijthe/Rtsne

Kruskal, J. B. (1964a). Multidimensional Scaling by Optimizing Goodness of Fit to a Nonmetric Hypothesis. Psychometrika, 29, 1–27.

Kruskal, J. B. (1964b). Nonmetric Multidimensional Scaling: A Numerical Method. Psychometrika, 29, 115–129.

Kruskal, J. B., & Wish, M. (1978). Multidimensional Scaling. Sage Publications.

Kuhn, M., & Wickham, H. (2020).

tidymodels: A Collection of Packages for Modeling and Machine Learning using tidyverse Principles. https://www.tidymodels.org

Kuhn, M., & Wickham, H. (2024).

tidymodels: Easily Install and Load the Tidymodels Packages.

https://tidymodels.tidymodels.org

Laa, U., Aumann, A., Cook, D., & Valencia, G. (2023). New and

Simplified

Manual

Controls for

Projection and

Slice

Tours,

With

Application to

Exploring

Classification

Boundaries in

High

Dimensions.

Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics,

32(3), 1229–1236.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10618600.2023.2206459

Laa, U., Cook, D., & Lee, S. (2022). Burning

Sage:

Reversing the

Curse of

Dimensionality in the

Visualization of

High-

Dimensional

Data.

Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics,

31(1), 40–49.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10618600.2021.1963264

Laa, U., Cook, D., & Valencia, G. (2020a). A

Slice

Tour for

Finding

Hollowness in

High-

Dimensional

Data.

Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics,

29(3), 681–687.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10618600.2020.1777140

Laa, U., Cook, D., & Valencia, G. (2020b). A

Slice

Tour for

Finding

Hollowness in

High-

Dimensional

Data.

Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics,

29(3), 681–687.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10618600.2020.1777140

Lancaster, H. O. (1965). The Helmert Matrices. The American Mathematical Monthly, 72(1), 4–12.

Laurent, S. (2023).

cxhull: Convex Hull.

https://github.com/stla/cxhull

Lee, E.-K. (2018). PPtreeViz: An

R package for

Visualizing

Projection

Pursuit

Classification

Trees.

Journal of Statistical Software,

83(8), 1–30.

https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v083.i08

Lee, E.-K., & Cook, D. (2009). A

Projection

Pursuit

Index for

Large

\(p\) Small

\(n\) Data.

Statistics and Computing,

20, 381–392.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11222-009-9131-1

Lee, E.-K., Cook, D., Klinke, S., & Lumley, T. (2005). Projection Pursuit for Exploratory Supervised Classification. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics, 14(4), 831–846.

Lee, S. (2021).

Liminal: Multivariate data visualization with tours and embeddings.

https://github.com/sa-lee/liminal/

Lee, S., Cook, D., Silva, N. da, Laa, U., Spyrison, N., Wang, E., & Zhang, H. S. (2022). The

State-of-the-

Art on

Tours for

Dynamic

Visualization of

High-

Dimensional

Data.

WIREs Computational Statistics,

14(4), e1573.

https://doi.org/10.1002/wics.1573

Lee, Y. D., Cook, D., Park, J., & Lee, E.-K. (2013).

PPtree: Projection Pursuit Classification Tree.

Electronic Journal of Statistics,

7(none), 1369–1386.

https://doi.org/10.1214/13-EJS810

Leisch, F. (2008). Visualizing

Cluster

Analysis and

Finite

Mixture

Models. In

Handbook of Data Visualization (pp. 561–587). Springer.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-33037-0_22

Li, M., Zhao, Z., & Scheidegger, C. (2020). Visualizing

Neural

Networks with the

Grand

Tour.

Distill.

https://doi.org/10.23915/distill.00025

Liaw, A., & Wiener, M. (2002). Classification and

Regression by

randomForest.

R News,

2(3), 18–22.

https://CRAN.R-project.org/doc/Rnews/

Littman, M. L., Swayne, D. F., Dean, N., & Buja, A. (1992). Visualizing the Embedding of Objects in Euclidean Space. Computing Science and Statistics: Proceedings of the 24th Symposium on the Interface, 208–217.

Lloyd, S. (1982). Least

Squares

Quantization in PCM.

IEEE Transactions on Information Theory,

28(2), 129–137.

https://doi.org/10.1109/TIT.1982.1056489

Longley, P. A., Maguire, D. J., Goodchild, M. F., & Rhind, D. W. (2005). Geographic Information Systems and Science. John Wiley & Sons.

Loperfido, N. (2018). Skewness-

Based

Projection

Pursuit: A

Computational

Approach.

Computational Statistics & Data Analysis,

120, 42–57. https://doi.org/

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csda.2017.11.001

Maaten, L. van der, & Hinton, G. (2008). Visualizing

Data

Using

t-SNE.

J. Mach. Learn. Res.,

9(Nov), 2579–2605.

http://www.jmlr.org/papers/v9/vandermaaten08a.html

MacQueen, J. B. (1967). Some Methods for Classification and Analysis of Multivariate Observations. In L. M. L. Cam & J. Neyman (Eds.), Proc. Of the fifth Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability (Vol. 1, pp. 281–297). University of California Press.

Maindonald, J., & Braun, J. (2003). Data Analysis and Graphics using R - an Example-based Approach. Cambridge University Press.

Martin, E. (1965). Flatland. http://www.der.org/films/flatland.html.

Mayer, M. (2024).

shapviz: SHAP visualizations.

https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=shapviz

Mayer, M., & Watson, D. (2023).

kernelshap: Kernel SHAP.

https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=kernelshap

McFarlane, M., & Young, F. W. (1994). Graphical Sensitivity Analysis for Multidimensional Scaling. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics, 3, 23–33.

McInnes, L., Healy, J., & Melville, J. (2018).

UMAP: Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection for Dimension Reduction.

http://arxiv.org/abs/1802.03426

McNeil, D. (1977). Interactive Data Analysis. John Wiley; Sons.

McVicar, T. (2011).

Near-Surface Wind Speed. v10. CSIRO. Data Collection. https://doi.org/10.25919/5c5106acbcb02

Meyer, D., Dimitriadou, E., Hornik, K., Weingessel, A., & Leisch, F. (2024).

e1071: Misc Functions of the Department of Statistics, Probability Theory Group (Formerly: E1071), TU Wien.

https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=e1071

Milborrow, S. (2024).

rpart.plot: Plot rpart Models: An Enhanced Version of plot.rpart.

http://www.milbo.org/rpart-plot/index.html

Molnar, C. (2025). Interpretable Machine Learning: A Guide for Making Black Box Models Explainable (3rd ed). https://christophm.github.io/interpretable-ml-book/.

Moon, K. R., Dijk, D. van, Wang, Z., Gigante, S., Burkhardt, D. B., Chen, W. S., Yim, K., Elzen, A. van den, Hirn, M. J., Coifman, R. R., Ivanova, N. B., Wolf, G., & Krishnaswamy, S. (2019). Visualizing

Structure and

Transitions for

Biological

Data

Exploration.

Nature Biotechnology,

37, 1482–1492.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-019-0336-3

Murrell, P. (2005). R Graphics. Chapman; Hall/CRC.

OpenStreetMap contributors. (2020).

Planet Dump Retrieved from https://planet.osm.org .

https://www.openstreetmap.org.

Pearson, K. (1901). LIII. On

Lines and

Planes of

Closest

Fit to

Systems of

Points in

Space.

The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science,

2(11), 559–572.

https://doi.org/10.1080/14786440109462720

Pedersen, T. L. (2024).

patchwork: The Composer of Plots.

https://patchwork.data-imaginist.com

Perisic, I., & Posse, C. (2005). Projection

Pursuit

Indices

Based on the

Empirical

Distribution

Function.

Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics,

14(3), 700–715.

https://doi.org/10.1198/106186005X69440

Polzehl, J. (1995). Projection Pursuit Discriminant Analysis. Computational Statistics and Data Analysis, 20, 141–157.

Posse, C. (1992). Projection Pursuit Discriminant Analysis for Two Groups. Communications in Statistics, Part A - Theory and Methods, 21, 1–19.

Posse, C. (1995). Tools for Two-dimensional Projection Pursuit. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics, 4(2), 83–100.

P-Tree System. (2020).

JAXA Himawari Monitor - User’s Guide.

https://www.eorc.jaxa.jp/ptree/userguide.html

R Core Team. (2023).

R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

https://www.R-project.org/

Rao, C. R. (1948). The Utilization of Multiple Measurements in Problems of Biological Classification (with discussion). Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B, 10, 159–203.

Rao, C. R. (Ed.). (1993). Handbook of Statistics, Vol. 9. Elsevier Science Publishers.

Rao, C. R., Wegman, E. J., & Solka, J. L. (Eds.). (2006). Handbook of Statistics: Data Mining and Visualization. Elsevier/North-Holland.

Ripley, B. (1996). Pattern Recognition and Neural Networks. Cambridge University Press.

Ripley, B. (2023).

nnet: Feed-Forward Neural Networks and Multinomial Log-Linear Models.

http://www.stats.ox.ac.uk/pub/MASS4/

Ripley, B., & Venables, B. (2024).

MASS: Support functions and datasets for venables and ripley’s MASS.

http://www.stats.ox.ac.uk/pub/MASS4/

Robinson, D., Hayes, A., & Couch, S. (2024).

broom: Convert Statistical Objects into Tidy Tibbles.

https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=broom

Rothkopf, E. Z. (1957). A

Measure of

Stimulus

Similarity and

Errors in

Some

Paired-

Associate

Learning

Tasks.

Journal of Experimental Psychology,

2, 94–101.

https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/h0041867

Roweis, S. T., & Saul, L. K. (2000). Nonlinear

Dimensionality

Reduction by

Locally

Linear

Embedding.

Science,

290(5500), 2323–2326.

https://doi.org/10.1126/science.290.5500.2323

Satija, R., Farrell, J. A., Gennert, D., Schier, A. F., & Regev, A. (2015). Spatial

Reconstruction of

Single-

Cell

Gene

Expression

Data.

Nature Biotechnology,

33, 495–502.

https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.3192

Savageau, D., & Boyer, R. (1993). Places Rated Almanac: Your Guide to Finding the Best Places to Live in North America. Prentce Hall Travel.

Schloerke, B. (2016).

geozoo: Zoo of Geometric Objects.

http://schloerke.github.io/geozoo/

Schloerke, B., Cook, D., Larmarange, J., Briatte, F., Marbach, M., Thoen, E., Elberg, A., & Crowley, J. (2024).

GGally: Extension to ggplot2.

https://ggobi.github.io/ggally/

Schloerke, B., Wickham, H., Cook, D., & Hofmann, H. (2016). Escape from Boxland. The R Journal, 8, 243–257.

Scrucca, L., Fraley, C., Murphy, T. B., & Raftery, A. E. (2023).

Model-Based Clustering, Classification, and Density Estimation Using mclust in R. Chapman; Hall/CRC.

https://doi.org/10.1201/9781003277965

Shepard, R. N. (1962). The Analysis of Proximities: Multidimensional Scaling with an Unknown Distance Function, I and II. Psychometrika, 27, 125-139 and 219-246.

Sievert, C. (2020).

Interactive Web-Based Data Visualization with R, plotly, and shiny. Chapman; Hall/CRC.

https://plotly-r.com

Sievert, C., Parmer, C., Hocking, T., Chamberlain, S., Ram, K., Corvellec, M., & Despouy, P. (2024).

plotly: Create Interactive Web Graphics via plotly.js.

https://plotly-r.com

Sjoberg, D. D., Larmarange, J., Curry, M., Lavery, J., Whiting, K., & Zabor, E. C. (2024).

Gtsummary: Presentation-ready data summary and analytic result tables.

https://github.com/ddsjoberg/gtsummary

Sjoberg, D. D., Whiting, K., Curry, M., Lavery, J. A., & Larmarange, J. (2021). Reproducible

Summary

Tables with the

gtsummary Package.

The R Journal,

13, 570–580.

https://doi.org/10.32614/RJ-2021-053

Slowikowski, K. (2024).

Ggrepel: Automatically position non-overlapping text labels with ggplot2.

https://ggrepel.slowkow.com/

Sparks, A. H., Carroll, J., Goldie, J., Marchiori, D., Melloy, P., Padgham, M., Parsonage, H., & Pembleton, K. (2020).

bomrang: Australian government bureau of meteorology (BOM) data client.

https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=bomrang

Spence, R. (2007). Information Visualization: Design for Interaction. Prentice Hall.

Stauffer, R., Mayr, G. J., Dabernig, M., & Zeileis, A. (2009).

Somewhere over the

Rainbow:

How to

Make

Effective

Use of

Colors in

Meteorological

Visualizations.

Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society,

96(2), 203–216.

https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-13-00155.1

Stuart, T., Butler, A., Hoffman, P., Hafemeister, C., Papalexi, E., III, W. M. M., Hao, Y., Stoeckius, M., Smibert, P., & Satija, R. (2019). Comprehensive

Integration of

Single-

Cell

Data.

Cell,

177, 1888–1902.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2019.05.031

Sutherland, P., Rossini, A., Lumley, T., Lewin-Koh, N., Dickerson, J., Cox, Z., & Cook, D. (2000). Orca: A

Visualization

Toolkit for

High-

Dimensional

Data.

Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics,

9(3), 509–529.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10618600.2000.10474896

Swayne, D. F., Buja, A., & Temple Lang, D. (2004). Exploratory Visual Analysis of Graphs in GGobi. In J. Antoch (Ed.), CompStat: Proceedings in computational statistics, 16th symposium. Physica-Verlag.

Swayne, D. F., Cook, D., & Buja, A. (1992). XGobi: Interactive Dynamic Graphics in the X Window System with a Link to S. American Statistical Association 1991 Proceedings of the Section on Statistical Graphics, 1–8.

Swayne, D. F., Cook, D., & Buja, A. (1998). XGobi:

Interactive

Dynamic

Data

Visualization in the

X Window

System.

Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics,

7(1), 113–130.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10618600.1998.10474764

Swayne, D. F., & Klinke, S. (1998). Editorial Commentary. Computational Statistics: Special Issue on The Use of Interactive Graphics, 14(1).

Swayne, D. F., Temple Lang, D., Buja, A., & Cook, D. (2003). GGobi: Evolving from XGobi into an Extensible Framework for Interactive Data Visualization. Computational Statistics & Data Analysis, 43, 423–444.

Swayne, D., & Buja, A. (1998). Missing Data in Interactive High-Dimensional Data Visualization. Computational Statistics, 13(1), 15–26.

Symanzik, J. (2002). New

Applications of the

Image

Grand

Tour.

Computing Science and Statistics,

34, 500--512.

https://math.usu.edu/symanzik/papers/2002_interface.pdf

Symanzik, J. (2004). Interactive and Dynamic Graphics. In J. E. Gentle, W. Härdle, & Y. Mori (Eds.), Handbook of Computational Statistics: Concepts and Methods (pp. 293–336). Springer.

Takatsuka, M., & Gahegan, M. (2002). GeoVISTA Studio: A Codeless Visual Programming Environment for Geoscientific Data Analysis and Visualization. The Journal of Computers and Geosciences, 28(10), 1131–1144.

Tang, Y., Horikoshi, M., & Li, W. (2016).

ggfortify:

Unified

Interface to

Visualize

Statistical

Result of

Popular

R Packages.

The R Journal,

8(2), 474–485.

https://doi.org/10.32614/RJ-2016-060

Tarpey, T., Li, L., & Flury, B. (1995). Principal Points and Self-Consistent Points of Elliptical Distributions. The Annals of Statistics, 23, 103–112.

Temple Lang, D., Swayne, D., Wickham, H., & Lawrence, M. (2006). rggobi: An Interface between R and GGobi. http://www.R-project.org.

Tenenbaum, J. B., Silva, V. de, & Langford, J. C. (2000). A

Global

Geometric

Framework for

Nonlinear

Dimensionality

Reduction.

Science,

290(5500), 2319–2323.

https://doi.org/10.1126/science.290.5500.2319

Therneau, T., & Atkinson, B. (2023).

rpart: Recursive Partitioning and Regression trees.

https://github.com/bethatkinson/rpart

Theus, M. (2002). Interactive Data Visualization Using Mondrian. Journal of Statistical Software, 7(11), http://www.jstatsoft.org.

Theus, M., Hofmann, H., & Wilhelm, A. F. X. (1998). Selection Sequences - Interactive Analysis of Massive Data Sets. Computing Science and Statistics, 29(1), 439–444.

Thompson, G. L. (1993). Generalized Permutation Polytopes and Exploratory Graphical Methods for Ranked Data. The Annals of Statistics, 21, 1401–1430.

Tierney, L. (1991). LispStat: An Object-Orientated Environment for Statistical Computing and Dynamic Graphics. John Wiley & Sons.

Tierney, N., & Cook, D. (2023a). Expanding

Tidy

Data

Principles to

Facilitate

Missing

Data

Exploration,

Visualization and

Assessment of

Imputations.

Journal of Statistical Software,

105(7), 1–31.

https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v105.i07

Tierney, N., & Cook, D. (2023b). Expanding

Tidy

Data

Principles to

Facilitate

Missing

Data

Exploration,

Visualization and

Assessment of

Imputations.

Journal of Statistical Software,

105(7), 1–31.

https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v105.i07

Tierney, N., Cook, D., McBain, M., & Fay, C. (2024).

naniar: Data Structures, Summaries, and Visualisations for Missing Data.

https://github.com/njtierney/naniar

Torgerson, W. S. (1952). Multidimensional Scaling. 1. Theory and Method. Psychometrika, 17, 401–419.

Tufte, E. (1983). The Visual Display of Quantitative Information. Graphics Press.

Tufte, E. (1990). Envisioning Information. Graphics Press.

Tukey, J. W. (1965). The Technical Tools of Statistics. The American Statistician, 19, 23–28.

Unwin, A. R., Hawkins, G., Hofmann, H., & Siegl, B. (1996). Interactive Graphics for Data Sets with Missing Values - MANET. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics, 5(2), 113–122.

Unwin, A., Hofmann, H., & Wilhelm, A. (2002). Direct Manipulation Graphics for Data Mining. Journal of Image and Graphics, 2(1), 49–65.

Unwin, A., Theus, M., & Hofmann, H. (2006). Graphics of Large Datasets: Visualizing a Million. Springer.

Unwin, A., Volinsky, C., & Winkler, S. (2003). Parallel

Coordinates for

Exploratory

Modelling

Analysis.

Comput. Stat. Data Anal.,

43(4), 553–564. https://doi.org/

{\tt http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0167-9473(02)00292-X}

Urbanek, S., & Theus, M. (2003). iPlots: High Interaction Graphics for R. In K. Hornik, F. Leisch, & A. Zeileis (Eds.), Proceedings of the 3rd international workshop on distributed statistical computing (DSC 2003).

Vaidyanathan, R., Xie, Y., Allaire, J., Cheng, J., Sievert, C., & Russell, K. (2023).

Htmlwidgets: HTML widgets for r.

https://github.com/ramnathv/htmlwidgets

van den Boogaart, K. G., Tolosana-Delgado, R., & Bren, M. (2024).

compositions: Compositional Data Analysis.

http://www.stat.boogaart.de/compositions/

van der Maaten, L. J. P. (2014). Accelerating t-SNE using Tree-Based lgorithms. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 15, 3221–3245.

van der Maaten, L. J. P., & Hinton, G. E. (2008). Visualizing High-Dimensional Data using t-SNE. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 9, 2579–2605.

Vapnik, V. N. (1999). The Nature of Statistical Learning Theory. Springer.

Velleman, P. F., & Velleman, A. Y. (1985). Data Desk Handbook. Data Description, Inc.

Venables, W. N., & Ripley, B. (2002).

Modern Applied Statistics with S. Springer-Verlag.

https://www.stats.ox.ac.uk/pub/MASS4/

Wainer, H. (2000). Visual Revelations (2nd ed). LEA, Inc.

Wainer, H., & Spence, I. (eds). (2005a). The Commercial and Political Atlas, Representing, by means of Stained Copper-Plate Charts, The Progress of the Commerce, Revenues, Expenditure, and Debts of England, during the whole of the Eighteenth Century, by William Playfair. Cambridge University Press.

Wainer, H., & Spence, I. (eds). (2005b). The Statistical Breviary; Shewing on a Principle entirely new, the resources of every state and kingdom in Europe; illustrated with Stained Copper-Plate Charts, representing the physical powers of each distinct nation with ease and perspicuity by William Playfair. Cambridge University Press.

Wang, P. C. C. (Ed.). (1978). Graphical Representation of Multivariate Data. Academic Press.

Wang, Y., Huang, H., Rudin, C., & Shaposhnik, Y. (2021). Understanding

How

Dimension

Reduction

Tools

Work: An

Empirical

Approach to

Deciphering

t-SNE,

UMAP,

TriMap, and

PaCMAP for

Data

Visualization.

Journal of Machine Learning Research,

22(201), 1–73.

http://jmlr.org/papers/v22/20-1061.html

Wegman, E. (1990). Hyperdimensional Data Analysis Using Parallel Coordinates. Journal of American Statistics Association, 85, 664–675.

Wegman, E. J. (1991). The Grand Tour in \(k\)-Dimensions (Technical Report No. 68). Center for Computational Statistics, George Mason University.

Wegman, E. J., & Carr, D. B. (1993). Statistical Graphics and Visualization (C. R. Rao, Ed.; pp. 857–958). Elsevier Science Publishers.

Wegman, E. J., Poston, W. L., & Solka, J. L. (1998). Image Grand Tour. Automatic Target Recognition VIII - Proceedings of SPIE, 3371, 286–294.

Wehrens, R., & Buydens, L. M. C. (2007). Self- and

Super-

Organizing

Maps in

R: The

kohonen package.

Journal of Statistical Software,

21(5), 1–19.

https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v021.i05

Wehrens, R., & Kruisselbrink, J. (2018). Flexible

Self-

Organizing

Maps in

kohonen 3.0.

Journal of Statistical Software,

87(7), 1–18.

https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v087.i07

Wehrens, R., & Kruisselbrink, J. (2023).

Kohonen: Supervised and unsupervised self-organising maps.

https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=kohonen

Wickham, H. (2016).

ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. Springer-Verlag New York.

https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org

Wickham, H. (2022).

classifly: Explore Classification Models in High Dimensions.

http://had.co.nz/classifly

Wickham, H., Chang, W., Henry, L., Pedersen, T. L., Takahashi, K., Wilke, C., Woo, K., Yutani, H., Dunnington, D., & van den Brand, T. (2024).

ggplot2: Create Elegant Data Visualisations Using the Grammar of Graphics.

https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org

Wickham, H., & Cook, D. (2025).

tourr: Tour Methods for Multivariate Data Visualisation.

https://github.com/ggobi/tourr

Wickham, H., Cook, D., & Hofmann, H. (2015). Visualizing

Statistical

Models:

Removing the

Blindfold.

Statistical Analysis and Data Mining: The ASA Data Science Journal,

8(4), 203–225.

https://doi.org/10.1002/sam.11271

Wickham, H., Cook, D., Hofmann, H., & Buja, A. (2011).

tourr:

An R Package for

Exploring Multivariate Data with

Projections.

Journal of Statistical Software,

40(2).

https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v040.i02

Wickham, H., François, R., Henry, L., Müller, K., & Vaughan, D. (2023).

dplyr: A Grammar of Data Manipulation.

https://dplyr.tidyverse.org

Wickham, H., Hester, J., & Bryan, J. (2024).

readr: Read Rectangular Text Data.

https://readr.tidyverse.org

Wilhelm, A. F. X., Wegman, E. J., & Symanzik, J. (1999). Visual Clustering and Classification: The Oronsay Particle Size Data Set Revisited. Computational Statistics: Special Issue on Interactive Graphical Data Analysis, 14(1), 109–146.

Wilkinson, L. (2005). The Grammar of Graphics. Springer.

Wills, G. (1999). NicheWorks - Interactive Visualization of Very Large Graphs. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics, 8(2), 190–212.

Xie, Y., Hofmann, H., & Cheng, X. (2014).

Reactive Programming for Interactive Graphics.

Statistical Science,

29(2), 201–213.

https://doi.org/10.1214/14-STS477

Young, F. W., Valero-Mora, P. M., & Friendly, M. (2006). Visual Statistics: Seeing Data with Dynamic Interactive Graphics. John Wiley & Sons.

Zeileis, A., Fisher, J. C., Hornik, K., Ihaka, R., McWhite, C. D., Murrell, P., Stauffer, R., & Wilke, C. O. (2020).

colorspace: A toolbox for manipulating and assessing colors and palettes.

Journal of Statistical Software,

96(1), 1–49.

https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v096.i01

Zeileis, A., Hornik, K., & Murrell, P. (2009). Escaping

RGBland:

Selecting

Colors for

Statistical

Graphics.

Computational Statistics & Data Analysis,

53(9), 3259–3270.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csda.2008.11.033

Zhang, C., Ye, J., & Wang, X. (2023). A

Computational

Perspective on

Projection

Pursuit in

High

Dimensions:

Feasible or

Infeasible

Feature

Extraction.

International Statistical Review,

91(1), 140–161.

https://doi.org/10.1111/insr.12517

Zhang, H. S., Cook, D., Laa, U., Langrené, N., & Menéndez, P. (2021). Visual

Diagnostics for

Constrained

Optimisation with

Application to

Guided

Tours.

The R Journal,

13(2), 624–641.

https://doi.org/10.32614/RJ-2021-105

Zhang, H. S., Cook, D., Laa, U., Langrené, N., & Menéndez, P. (2024).

ferrn: Facilitate Exploration of touRR optimisatioN.

https://github.com/huizezhang-sherry/ferrn/